Dragons in History

“The

dragons of legend are strangely like actual creatures that have lived

in the past. They are much like the great reptiles which inhabited the

earth long before man is supposed to have appeared on earth. Dragons

were generally evil and destructive. Every country had them in its

mythology.” (Knox, Wilson, “Dragon,” The World Book Encyclopedia, vol. 5, 1973, p. 265.) The article on dragons in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1949

edition) noted that dinosaurs were “astonishingly dragonlike,” even

though its author assumed that those ancients who believed in dragons

did so “without the slightest knowledge” of dinosaurs. The truth is that

the fathers of modern paleontology used the terms “dinosaur” and

“dragon” interchangeably for quite some time.

“The

dragons of legend are strangely like actual creatures that have lived

in the past. They are much like the great reptiles which inhabited the

earth long before man is supposed to have appeared on earth. Dragons

were generally evil and destructive. Every country had them in its

mythology.” (Knox, Wilson, “Dragon,” The World Book Encyclopedia, vol. 5, 1973, p. 265.) The article on dragons in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1949

edition) noted that dinosaurs were “astonishingly dragonlike,” even

though its author assumed that those ancients who believed in dragons

did so “without the slightest knowledge” of dinosaurs. The truth is that

the fathers of modern paleontology used the terms “dinosaur” and

“dragon” interchangeably for quite some time. Stories

of dragons have been handed down for generations in many civilizations.

No doubt many of these stories have been exaggerated through the years.

But that does not mean they had no original basis in fact. Even some

living lizards look like dragons and it is easy to see how a larger

variety of such an animal could frighten a community. Have you ever seen

an old dinosaur film where they used an iguana in a miniature town set

to create the illusion of a great dragon?

Stories

of dragons have been handed down for generations in many civilizations.

No doubt many of these stories have been exaggerated through the years.

But that does not mean they had no original basis in fact. Even some

living lizards look like dragons and it is easy to see how a larger

variety of such an animal could frighten a community. Have you ever seen

an old dinosaur film where they used an iguana in a miniature town set

to create the illusion of a great dragon? In

2004 a fascinating dinosaur skull was donated to the Children’s Museum

of Indianapolis by three Sioux City, Iowa, residents who found it during

a trip to the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota. The trio are still

excavating the site, looking for more of the dinosaur’s bones. Because

of its dragon-like head, horns and teeth, the new species was dubbed Dracorex

hogwartsia. This name honors the Harry Potter fictional works, which

features the Hogwarts School and recently popularized dragons. The

dinosaur’s skull mixes spiky horns, bumps and a long muzzle. But unlike

other members of the pachycephalosaur family, which have domed

foreheads, this one is flat-headed. Consider some of the ancient stories

of dragons, some fictional and some that might be authentic history of

dinosaurs.

In

2004 a fascinating dinosaur skull was donated to the Children’s Museum

of Indianapolis by three Sioux City, Iowa, residents who found it during

a trip to the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota. The trio are still

excavating the site, looking for more of the dinosaur’s bones. Because

of its dragon-like head, horns and teeth, the new species was dubbed Dracorex

hogwartsia. This name honors the Harry Potter fictional works, which

features the Hogwarts School and recently popularized dragons. The

dinosaur’s skull mixes spiky horns, bumps and a long muzzle. But unlike

other members of the pachycephalosaur family, which have domed

foreheads, this one is flat-headed. Consider some of the ancient stories

of dragons, some fictional and some that might be authentic history of

dinosaurs. Written about 2,000 B.C. the famous Epic of Gilgamesh

records the slaying of the monster Humbaba in Mesopotamia. Humbaba was

the terrifying guardian of the Cedar Forest of Amanus. The powerful

Mesopotamian god Enlil placed Humbaba there to kill any human that dared

disturb its peace. Humbaba was a giant creature, terrifying to look at.

Sometimes he is pictured as a large, humanoid shape covered with scale

plates. His powerful legs were like that of a lion, but with the talons

of a vulture. His head had bull’s horns and his tail was like a serpent.

Alternatively, some sources give Humbaba the form of a dragon that

could breathe fire. (Drawing to the left by Fafnirx.)

Written about 2,000 B.C. the famous Epic of Gilgamesh

records the slaying of the monster Humbaba in Mesopotamia. Humbaba was

the terrifying guardian of the Cedar Forest of Amanus. The powerful

Mesopotamian god Enlil placed Humbaba there to kill any human that dared

disturb its peace. Humbaba was a giant creature, terrifying to look at.

Sometimes he is pictured as a large, humanoid shape covered with scale

plates. His powerful legs were like that of a lion, but with the talons

of a vulture. His head had bull’s horns and his tail was like a serpent.

Alternatively, some sources give Humbaba the form of a dragon that

could breathe fire. (Drawing to the left by Fafnirx.)Daniel was said to kill a dragon in the apocryphal chapters of the Bible. After Alexander the Great invaded India he brought back reports of seeing a great hissing dragon living in a cave. Later Greek rulers supposedly brought dragons alive from Ethiopia. (Gould, Charles,Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1886, pp. 382-383.) Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia (“Dinosaur” entry) explains that the historical references to dinosaur bones may extend as far back as the 5th century BC. In fact, some scholars think that the Greek historian Herodotus was referring to fossilized dinosaur skeletons and eggs when he described griffins guarding nests in central Asia. “Dragon bones” mentioned in a 3rd century AD text from China are thought to refer to bones of dinosaurs.

Ancient explorers and historians, like Josephus, told of small flying reptiles in ancient Egypt and Arabia and described their predators, the ibis, stopping their invasion into Egypt. (Epstei+n, Perle S., Monsters: Their Histories, Homes, and Habits, 1973, p.43.) A third century historian Gaius Solinus, discussed the Arabian flying serpents, and stated that “the poison is so quick that death follows before pain can be felt.” (Cobbin, Ingram, Condensed Commentary and Family Exposition on the Whole Bible, 1837, p. 171.) The well-respected Greek researcher Herodotus wrote: “There is a place in Arabia, situated very near the city of Buto, to which I went, on hearing of some winged serpents; and when I arrived there, I saw bones and spines of serpents, in such quantities as it would be impossible to describe. The form of the serpent is like that of the water-snake; but he has wings without feathers, and as like as possible to the wings of a bat.” (Herodotus, Historiae, tr. Henry Clay, 1850, pp. 75-76.) Herodotus has been called “the Father of History” because he was the first historian we know who collected his materials systematically and then tested them for accuracy. John Goertzen noted the Egyptian representation of tail vanes with flying reptiles and concluded that they must have observed pterosaurs or they would not have known to sketch this leaf-shaped tail. He also matched a flying reptile, observed in Egypt and sketched by the outstanding Renaissance scientist Pierre Belon, with the Dimorphodon genus of pterosaur. (Goertzen, J.C., “Shadows of Rhamphorhynchoid Pterosaurs in Ancient Egypt and Nubia,” Cryptozoology, Vol 13, 1998.)

Charles Gould cites the historian Gesner as saying that, “In 1543, a kind of dragon appeared near Styria, within the confines of Germany, which had feet like lizards, and wings after the fashion of a bat, with an incurable bite… He refers to a description by Scaliger (Scaliger, lib. III. Miscellaneous cap. i, “Winged Serpents,” p. 182.) of a species of serpent four feet long, and as thick as a man’s arm, with cartilaginous wings pendent from the sides. He also mentions Brodeus, of a winged dragon which was brought to Francis, the invincible King of the Gauls, by a countryman who had killed it with a mattock near Sanctones, and which was stated to have been seen by many men of approved reputation, who though it had migrated from transmarine regions by the assistance of the wind. Cardan (De Natura Rerum, lib VII, cap. 29.) states that whilst he resided in Paris he saw five winged dragons in the WilliamMuseum; these were biped, and possessed of wings so slender that it was hardly possible that they could fly with them. Cardan doubted their having been fabricated, since they had been sent in vessels at different times, and yet all presented the same

remarkable

form. Bellonius states that he had seen whole carcases [sic] of winged

dragons, carefully prepared, which he considered to be of the same kind

as those which fly out of Arabia into Egypt; they were thick about the

belly, had two feet, and two wings, whole like those of a bat, and a

snake’s tail.” (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen

& Co., London, 1886, pp. 136-138.) The Italian historian Aldrovandus

also claimed to have received in the year 1551 a “true dried Aethiopian

dragon” a watercolor of which appears to the right. At first glance,

one is tempted agree with Gould that the wings are ridiculously small.

But perhaps in transporting from Ethiopia the wings broke off or dried

to dust and thus had to be added from the artist’s imagination.

remarkable

form. Bellonius states that he had seen whole carcases [sic] of winged

dragons, carefully prepared, which he considered to be of the same kind

as those which fly out of Arabia into Egypt; they were thick about the

belly, had two feet, and two wings, whole like those of a bat, and a

snake’s tail.” (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen

& Co., London, 1886, pp. 136-138.) The Italian historian Aldrovandus

also claimed to have received in the year 1551 a “true dried Aethiopian

dragon” a watercolor of which appears to the right. At first glance,

one is tempted agree with Gould that the wings are ridiculously small.

But perhaps in transporting from Ethiopia the wings broke off or dried

to dust and thus had to be added from the artist’s imagination.The first century Greek historian Strabo, who traveled and researched extensively throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, wrote a treatise on geography. He explained that in India “there are reptiles two cubits long with membranous wings like bats, and that they too fly by night, discharging drops of urine, or also of sweat, which putrefy the skin of anyone who is not on his guard;” (Strabo, Geography: Book XV: “On India,” Chap. 1, No. 37, AD 17, pp. 97-98.) Strabos account may have been based in part on the earlier work of Megasthenes (ca 350 – 290 BC) who traveled to India and states that there are “snakes (ophies) with wings, and that their visitations occur not during the daytime but by night, and that they emit urine which at once produces a festering wound on any body on which it may happen to drop.” (Aelianus, Greek Natural History:On Animals, 3rd century AD, 16.41.)

The

Chinese have many stories of dragons. Some ornamental pictures of

dragons are shaped remarkably like dinosaurs. Marco Polo wrote of his

travels to the province of Karajan and reported on huge serpents, which

at the fore part have two short legs, each with three claws. “The jaws

are wide enough to swallow a man, the teeth are large and sharp, and

their whole appearance is so formidable that neither man, nor any kind

of animal can approach them without terror.” (Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo,

1961, pp. 158-159.) Books even tell of Chinese families raising dragons

to use their blood for medicines and highly prizing their eggs.

(DeVisser, Marinus Willem, The Dragon in China & Japan, 1969.) To the top right are pictures of a fossilized dinosaur egg compared to a chicken egg and a Protoceratops

dinosaur eggs that is double-yoked. It is interesting that the twelve

signs of the Chinese zodiac are all animals–eleven of which are still

alive today.

The

Chinese have many stories of dragons. Some ornamental pictures of

dragons are shaped remarkably like dinosaurs. Marco Polo wrote of his

travels to the province of Karajan and reported on huge serpents, which

at the fore part have two short legs, each with three claws. “The jaws

are wide enough to swallow a man, the teeth are large and sharp, and

their whole appearance is so formidable that neither man, nor any kind

of animal can approach them without terror.” (Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo,

1961, pp. 158-159.) Books even tell of Chinese families raising dragons

to use their blood for medicines and highly prizing their eggs.

(DeVisser, Marinus Willem, The Dragon in China & Japan, 1969.) To the top right are pictures of a fossilized dinosaur egg compared to a chicken egg and a Protoceratops

dinosaur eggs that is double-yoked. It is interesting that the twelve

signs of the Chinese zodiac are all animals–eleven of which are still

alive today.

But

is the twelfth, the dragon merely a legend or is it based on a real

animal– the dinosaur? It doesn’t seem logical that the ancient Chinese,

when constructing their zodiac, would include one mythical animal with

eleven real animals. ”The interpretation of dinosaurs as dragons goes

back more than two thousand years in Chinese culture. They were regarded

as sacred, as a symbol of power…” (Zhiming, Doug, Dinosaurs From China,

1988, p. 9.) Shown here are dragons that were cast in red gold and

embossed during the Tang Dynasty (618-906 AD). Notice the long neck and

tail, the frills, and the lithe stance.

But

is the twelfth, the dragon merely a legend or is it based on a real

animal– the dinosaur? It doesn’t seem logical that the ancient Chinese,

when constructing their zodiac, would include one mythical animal with

eleven real animals. ”The interpretation of dinosaurs as dragons goes

back more than two thousand years in Chinese culture. They were regarded

as sacred, as a symbol of power…” (Zhiming, Doug, Dinosaurs From China,

1988, p. 9.) Shown here are dragons that were cast in red gold and

embossed during the Tang Dynasty (618-906 AD). Notice the long neck and

tail, the frills, and the lithe stance.St. John of Damascus, an eastern monk who wrote in the 8th century, gives a sober account of dragons, insisting that they are mere reptiles and did not have magical powers. He quotes of the Roman historian Dio who chronicled the Roman empire in the second century. It seems Regulus, a Roman consul, fought against Carthage, when a dragon suddenly crept up and settled behind the wall of the Roman army. The Romans killed it, skinned it and sent the hide to the Roman Senate. Dio claimed the hide was measured by order of the senate and found to be one hundred and twenty feet long. It seems unlikely that either Dio or the pious St. John would support an outright fabrication involving a Roman consul and the Senate.

“Among Serpents, we find some that are furnished with Wings. Herodotus who saw those Serpents, says they had great Resemblance to those which the Greeks and Latins call’d Hydra; their Wings are not compos’d of Feathers like the Wings of Birds, but rather like to those of Batts; they love sweet smells, and frequent such Trees as bear Spices. These were the fiery Serpents that made so great a Destruction in the Camp of Israel…The brazen Serpent was a Figure of the flying Serpent, Saraph, which Moses fixed upon an erected Pole: That there were such, is most evident. Herodotus who had seen of those Serpents, says they very much resembled those which the Greeks and Latins called Hydra: He went on purpose to the City of Brutus to see those flying Animals, that had been devour’d by the Ibidian Birds.” (Owen, Charles, An Essay Towards a Natural History of Serpents, 1742, pp. 191-193.)

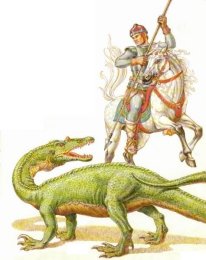

In

medieval times, the Scandinavians described swimming dragons and the

Vikings placed dragons on the front of their ships to scare off the sea

monsters. The one pictured to the right is based upon the 1734 sighting

by Hans Egede. As a missionary to Greenland, Egede was known as a

meticulous recorder of the natural world. Numerous such stories have

been recorded from the age of sailing ships (1500-1900 A.D.). The

familiar story of Beowulf and the legend of Saint George slaying a

dragon, which are well-known in the annals of English literature, likely

have some basis in fact. Indeed the “dragon” pictured to the left is

the dinosaur Baryonyx, whose skeleton has been found in England. Dragons

were even described in reputable zoological treatises published during

the Middle Ages. For example, the great Swiss naturalist and medical

doctor Konrad Gesner published a four-volume encyclopedia from 1516-1565

entitled Historiae Animalium. He mentioned dragons as “very rare but still living creatures.” (p.224)

In

medieval times, the Scandinavians described swimming dragons and the

Vikings placed dragons on the front of their ships to scare off the sea

monsters. The one pictured to the right is based upon the 1734 sighting

by Hans Egede. As a missionary to Greenland, Egede was known as a

meticulous recorder of the natural world. Numerous such stories have

been recorded from the age of sailing ships (1500-1900 A.D.). The

familiar story of Beowulf and the legend of Saint George slaying a

dragon, which are well-known in the annals of English literature, likely

have some basis in fact. Indeed the “dragon” pictured to the left is

the dinosaur Baryonyx, whose skeleton has been found in England. Dragons

were even described in reputable zoological treatises published during

the Middle Ages. For example, the great Swiss naturalist and medical

doctor Konrad Gesner published a four-volume encyclopedia from 1516-1565

entitled Historiae Animalium. He mentioned dragons as “very rare but still living creatures.” (p.224) The city of Nerluc in France was renamed in honor of the killing of a “dragon” there. (Picture from Taylor, Paul, The Great Dinosaur Mystery,

1989, p. 40.) This animal was said to be bigger than an ox and had

long, sharp, pointed horns on its head. Was this a surviving

Triceratops? The story is told of a tenth century Irishman who

encountered a large clawed beast having “iron on its tail which pointed

backwards.” It had a head similar to a horse. It also had thick legs and

strong claws. Could this have been a remaining Stegosaurus? (Ham, K., The Great Dinosaur Mystery Solved, 1999, p.33

The city of Nerluc in France was renamed in honor of the killing of a “dragon” there. (Picture from Taylor, Paul, The Great Dinosaur Mystery,

1989, p. 40.) This animal was said to be bigger than an ox and had

long, sharp, pointed horns on its head. Was this a surviving

Triceratops? The story is told of a tenth century Irishman who

encountered a large clawed beast having “iron on its tail which pointed

backwards.” It had a head similar to a horse. It also had thick legs and

strong claws. Could this have been a remaining Stegosaurus? (Ham, K., The Great Dinosaur Mystery Solved, 1999, p.33 Ulysses

Aldrovandus is considered by many to be the father of modern natural

history. He traveled extensively, collected thousands of animals and

plants, and created the first ever natural history museum. His

impressive collections are still on display at the Bologna University

(the world’s oldest university) where they attest to his scholarship.

His credentials give credence to an incident that Aldrovandus personally

reported concerning a dragon. The dragon was first seen on May 13,

1572, hissing like a snake. He had been hiding on the small estate of

Master Petronius. At 5:00 PM, the dragon was caught on a public roadway

by a herdsman named Baptista, near the hedge of a private farm, a mile

from the remote city outskirts of Bologna. Baptista was following his ox

cart home when he noticed the oxen suddenly come to a stop. He kicked

them and shouted at them, but they refused to move and went down on

their knees rather than move forward.

Ulysses

Aldrovandus is considered by many to be the father of modern natural

history. He traveled extensively, collected thousands of animals and

plants, and created the first ever natural history museum. His

impressive collections are still on display at the Bologna University

(the world’s oldest university) where they attest to his scholarship.

His credentials give credence to an incident that Aldrovandus personally

reported concerning a dragon. The dragon was first seen on May 13,

1572, hissing like a snake. He had been hiding on the small estate of

Master Petronius. At 5:00 PM, the dragon was caught on a public roadway

by a herdsman named Baptista, near the hedge of a private farm, a mile

from the remote city outskirts of Bologna. Baptista was following his ox

cart home when he noticed the oxen suddenly come to a stop. He kicked

them and shouted at them, but they refused to move and went down on

their knees rather than move forward.  At

this point, the herdsman noticed a hissing sound and was startled to

see this strange little dragon ahead of him.Trembling he struck it on

the head with his rod and killed it. (Aldrovandus, Ulysses, The Natural History of Serpents and Dragons,

1640, p.402.) Aldrovandus surmised that dragon was a juvenile, judging

by the incompletely developed claws and teeth.The corpse had only two

feet and moved both by slithering like a snake and by using its feet, he

believed. (There are small two-legged lizards that do this today.)

Aldrovandus mounted the specimen and displayed it for some time. He also

had a watercolor painting of the creature made (see upper left).

At

this point, the herdsman noticed a hissing sound and was startled to

see this strange little dragon ahead of him.Trembling he struck it on

the head with his rod and killed it. (Aldrovandus, Ulysses, The Natural History of Serpents and Dragons,

1640, p.402.) Aldrovandus surmised that dragon was a juvenile, judging

by the incompletely developed claws and teeth.The corpse had only two

feet and moved both by slithering like a snake and by using its feet, he

believed. (There are small two-legged lizards that do this today.)

Aldrovandus mounted the specimen and displayed it for some time. He also

had a watercolor painting of the creature made (see upper left). In

medieval times, scientifically minded authors produced volumes called

“bestiaries,” a compilation of known (and sometimes imaginary) animals

accompanied by a moralizing explanation and fascinating pictures. One

such volume is the Aberdeen Bestiary, written in the early

1500s and preserved in the library of Henry VIII. Along with the newt,

the salamander, and various kinds of snakes is the description and

depiction of the dragon: “The dragon is bigger than all other snakes or

all other living things on earth. For this reason, the Greeks call it

dracon, from this is derived its Latin name draco. The dragon, it is

said, is often drawn forth from caves into the open air, causing the air

to become turbulent. The dragon has a crest, a small mouth, and narrow

blow-holes through which it breathes and puts forth its tongue. Its

strength lies not in its teeth but in its tail, and it kills with a blow

rather than a bite. It is free from poison. They say that it does not

need poison to kill things, because it kills anything around which it

wraps its tail. From the dragon not even the elephant, with its huge

size, is safe. For lurking on paths along which elephants are accustomed

to pass, the dragon knots its tail around their legs and kills them by

suffocation. Dragons are born in Ethiopia and India, where it is hot all

year round.” Flavious Philostratus, the third century historian

provided this sober account: “The whole of India is girt with dragons of

enormous size; for not only the marshes are full of them, but the

mountains as well, and there is not a single ridge without one. Now the

marsh kind are sluggish in their habits and are thirty cubits long, and

they have no crest standing up on their heads.” (Philostratus, Flavius, The Life of Apollonius of Tyanna, 170 AD.) Pliny the Elder also referenced large dragons in India in his Natural History.

In

medieval times, scientifically minded authors produced volumes called

“bestiaries,” a compilation of known (and sometimes imaginary) animals

accompanied by a moralizing explanation and fascinating pictures. One

such volume is the Aberdeen Bestiary, written in the early

1500s and preserved in the library of Henry VIII. Along with the newt,

the salamander, and various kinds of snakes is the description and

depiction of the dragon: “The dragon is bigger than all other snakes or

all other living things on earth. For this reason, the Greeks call it

dracon, from this is derived its Latin name draco. The dragon, it is

said, is often drawn forth from caves into the open air, causing the air

to become turbulent. The dragon has a crest, a small mouth, and narrow

blow-holes through which it breathes and puts forth its tongue. Its

strength lies not in its teeth but in its tail, and it kills with a blow

rather than a bite. It is free from poison. They say that it does not

need poison to kill things, because it kills anything around which it

wraps its tail. From the dragon not even the elephant, with its huge

size, is safe. For lurking on paths along which elephants are accustomed

to pass, the dragon knots its tail around their legs and kills them by

suffocation. Dragons are born in Ethiopia and India, where it is hot all

year round.” Flavious Philostratus, the third century historian

provided this sober account: “The whole of India is girt with dragons of

enormous size; for not only the marshes are full of them, but the

mountains as well, and there is not a single ridge without one. Now the

marsh kind are sluggish in their habits and are thirty cubits long, and

they have no crest standing up on their heads.” (Philostratus, Flavius, The Life of Apollonius of Tyanna, 170 AD.) Pliny the Elder also referenced large dragons in India in his Natural History.The 16th century Italian explorer Pigafetta, in a report of the kingdom of Congo, described the province of Bemba, which he defines as “on the sea coast from the river Ambrize, until the river Coanza towards the south,” and says of serpents, “There are also certain other creatures which, being as big as rams, have wings like dragons, with long tails, and long chaps, and divers rows of teeth, and feed upon raw flesh. Their colour is blue and green, their skin painted like scales, and they have two feet but no more. The Pagan negroes used to worship them as gods, and to this day you may see divers of them that are kept for a marvel. And because they are very rare, the chief lords there curiously preserve them, and suffer the people to worship them, which tendeth greatly to their profits by reason of the gifts and oblations which the people offer unto them.” (Pigafetta, Filippo, The Harleian Collections of Travels, vol. ii, 1745, p. 457.)

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle gives a dire entry for the year 793. (In those days it was common to take glowing, flying dragon activity as an omen of evil to come.) “This year came dreadful fore-warnings over the land of the Northumbrians, terrifying the people most woefully: these were immense sheets of light rushing through the air, and whirlwinds, and fiery, dragons flying across the firmament.” Reliable witness reports of “flying dragons” (pterosaur-like creatures) in Europe are recorded around 1649. (Thorpe, B. Ed., The Anglo Saxon Chronicle, 1861, p.48.)

The woods around Penllyn Castle, Glamorgan, had the reputation of being frequented by winged serpents, and these were the terror of old and young alike. An aged inhabitant of Penllyn, who died a few years ago, said that in his boyhood the winged serpents were described as very beautiful. They were coiled when in repose, and “looked as if they were covered with jewels of all sorts. Some of them had crests sparkling with all the colours of the rainbow”. When disturbed they glided swiftly, “sparkling all over,” to their hiding places. When angry, they “flew over people’s heads, with outspread wings, bright, and sometimes with eyes too, like the feathers in a peacock’s tail”. He said it was “no old story invented to frighten children”, but a real fact. His father and uncle had killed some of them, for they were as bad as foxes for poultry. The old man attributed the extinction of the winged serpents to the fact that they were “terrors in the farmyards and coverts.” (Trevelyan, Marie, 1909, Folk-Lore and Folk Stories of Wales, p. 168-169.)

An

example of an ancient dragon story is given to the right (click to

enlarge and read some text.) The prolific 17th century writer Athanasius

Kircher’s record tells how the noble man, Christopher Schorerum,

prefect of the entire territory, “wrote a true history summarizing there

all, for by that way, he was able to confirm the truth of the things

experienced, and indeed the things truly seen by the eye, written in his

own words: “On a warm night in 1619, while contemplating the serenity

of the heavens, I saw a shining dragon of great size in front of Mt.

Pilatus, coming from the opposite side of the lake [or 'hollow'], a cave

that is named Flue [Hogarth-near Lucerne] moving rapidly in an agitated

way, seen flying across; It was of a large size, with a long tail, a

long neck, a reptile’s head, and ferocious gaping jaws. As it flew it

was like iron struck in a forge when pressed together that scatters

sparks. At first I thought it was a meteor from what I saw. But after I

diligently observed it alone, I understood it was indeed a dragon from

the motion of the limbs of the entire body.” From the writings of a

respected clergyman, in fact a dragon truely exists in nature it is

amply established.” (Kircher, Athanasius, Mundus Subterraneus,

1664, tr. by Hogarth, “Dragons,” 1979, pp. 179-180.) Such bioluminescent

nocturnal flying creatures are known in some regions still today. (See

the Ropen page.) Might they not be the basis for the “fiery dragon” lore from ancient civilizations around the world?

An

example of an ancient dragon story is given to the right (click to

enlarge and read some text.) The prolific 17th century writer Athanasius

Kircher’s record tells how the noble man, Christopher Schorerum,

prefect of the entire territory, “wrote a true history summarizing there

all, for by that way, he was able to confirm the truth of the things

experienced, and indeed the things truly seen by the eye, written in his

own words: “On a warm night in 1619, while contemplating the serenity

of the heavens, I saw a shining dragon of great size in front of Mt.

Pilatus, coming from the opposite side of the lake [or 'hollow'], a cave

that is named Flue [Hogarth-near Lucerne] moving rapidly in an agitated

way, seen flying across; It was of a large size, with a long tail, a

long neck, a reptile’s head, and ferocious gaping jaws. As it flew it

was like iron struck in a forge when pressed together that scatters

sparks. At first I thought it was a meteor from what I saw. But after I

diligently observed it alone, I understood it was indeed a dragon from

the motion of the limbs of the entire body.” From the writings of a

respected clergyman, in fact a dragon truely exists in nature it is

amply established.” (Kircher, Athanasius, Mundus Subterraneus,

1664, tr. by Hogarth, “Dragons,” 1979, pp. 179-180.) Such bioluminescent

nocturnal flying creatures are known in some regions still today. (See

the Ropen page.) Might they not be the basis for the “fiery dragon” lore from ancient civilizations around the world?John Harris was a scientific man that edited the first encyclopedia. He gives a singularly account of the capture of a dragon: “We have, in an ancient author, a very large and circumstantial account of the taking of a dragon on the frontiers of Ethiopia, which was one and twenty feet in length, and was carried to Ptolemy Philadelphus, who every bountifully rewarded such as ran the hazard of procuring him this beast.” (Harris, John, Collection of Voyages, vol. i, London, 1764, p. 474.) But this pales in comparison to the account St. Ambrose gives of dragons “seen in the neighbourhood of the Ganges nearly seventy cubits in length.” (Ambrose, De Moribus Brachmanorum, 1668.) It was one of this size that Alexander and his army saw in a cave. “Its terrible hissing made a strong impression on the Macedonians, who, with all their courage, could not help being frighted at so horrid a spectacle.” (Aelian, De Animal, lib. XV, cap. 21.)

Gould sought to dispel supernatural notions and give a sober account of the dragon. “The dragon is nothing more than a serpent of enormous size; and they formerly distinguished three sorts of them in the Indies. Viz. such as were in the mountains, such as were bred in the caves or in the flat country, and such as were found in fens and marshes. The first is the largest of all, and are covered with scales as resplendent as polished gold. These have a kind of beard hanging from their lower jaw, their eyebrows large, and very exactly arched; their aspect the most frightful that can be imagined, and their cry loud and shrill… their crests of a bright yellow, and a protuberance on their heads of the colour of a burning coal. Those of the flat country differ from the former in nothing but in having their scales of a silver colour, and in their frequenting rivers, to which the former never come. Those that live in marshes and fens are of a dark colour, approaching to a black, move slowly, have no crest, or any rising upon their heads.” (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1886, p. 140.)

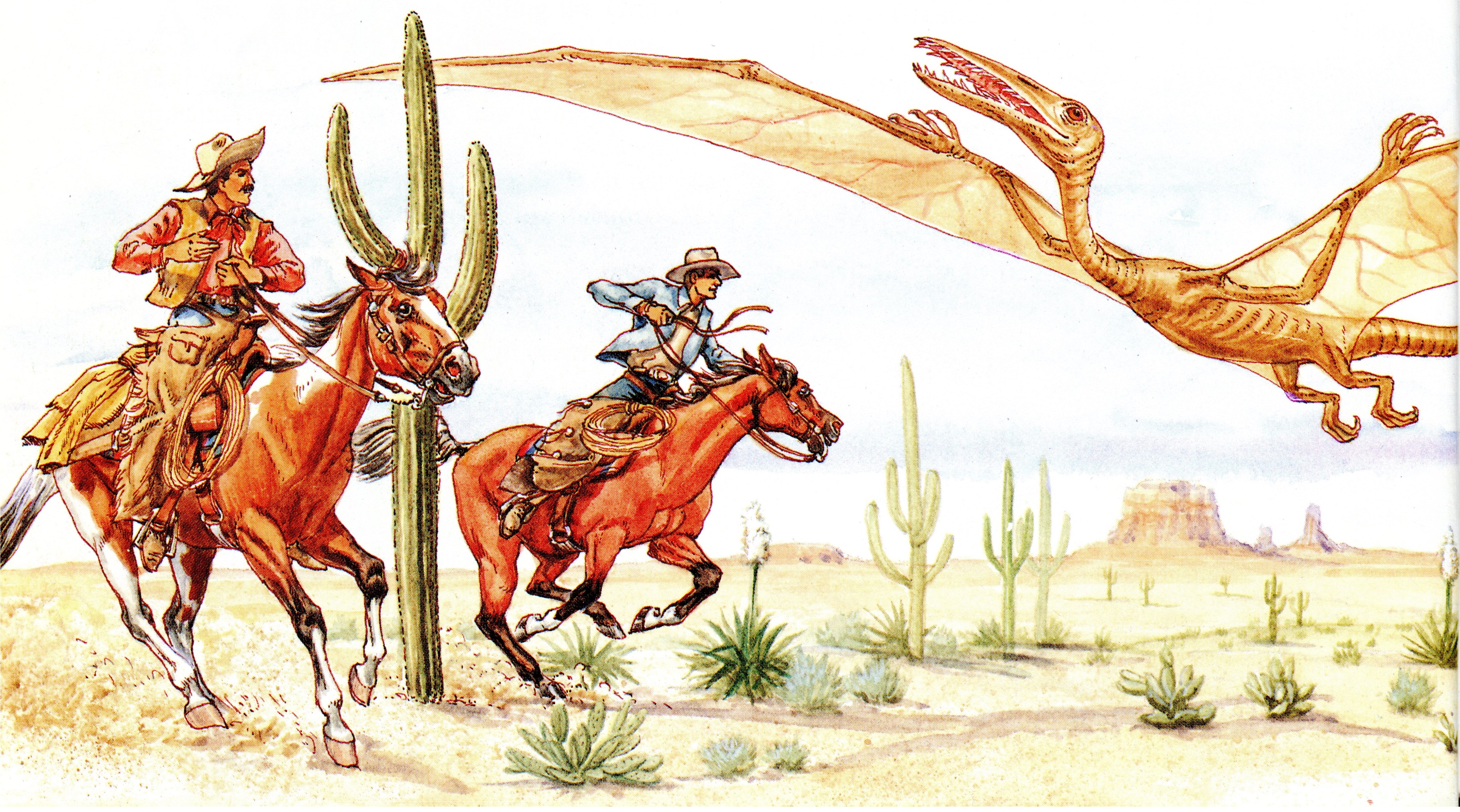

On

April 26, 1890 the Tombstone Epitaph (a local Arizona newspaper)

reported that two cowboys had discovered and shot down a creature –

described as a “winged dragon” – which resembled a pterodactyl, only

MUCH larger. The cowboys said its wingspan was 160 feet, and that its

body was more than four feet wide and 92 feet long. The cowboys

supposedly cut off the end of the wing to prove the existence of the

creature. The paper’s description of the animal fits the Quetzelcoatlus,

whose fossils were found in Texas. (Gish, Dinosaurs by Design,

1992, p. 16.) Could this be thunderbird or Wakinyan, the jagged-winged,

fierce-toothed flying creature of Sioux American Indian legend? This

thunderbird supposedly lived in a cave on the top of the Olympic

Mountains and feasted on seafood. Different from the eagle (Wanbli) or

hawk (Cetan) the Wakinyan was said to be huge, carrying off children,

and was named because of its association with thunder and

lightning–supposedly being struck by lightning and seen to fall to the

ground during a storm. (Geis, Darlene, Dinosaurs & Other Prehistoric Animals, 1959, p. 9.) It was further distinguished by its piercing cry and thunderous beating wings (Lame Deer’s 1969 interview).

On

April 26, 1890 the Tombstone Epitaph (a local Arizona newspaper)

reported that two cowboys had discovered and shot down a creature –

described as a “winged dragon” – which resembled a pterodactyl, only

MUCH larger. The cowboys said its wingspan was 160 feet, and that its

body was more than four feet wide and 92 feet long. The cowboys

supposedly cut off the end of the wing to prove the existence of the

creature. The paper’s description of the animal fits the Quetzelcoatlus,

whose fossils were found in Texas. (Gish, Dinosaurs by Design,

1992, p. 16.) Could this be thunderbird or Wakinyan, the jagged-winged,

fierce-toothed flying creature of Sioux American Indian legend? This

thunderbird supposedly lived in a cave on the top of the Olympic

Mountains and feasted on seafood. Different from the eagle (Wanbli) or

hawk (Cetan) the Wakinyan was said to be huge, carrying off children,

and was named because of its association with thunder and

lightning–supposedly being struck by lightning and seen to fall to the

ground during a storm. (Geis, Darlene, Dinosaurs & Other Prehistoric Animals, 1959, p. 9.) It was further distinguished by its piercing cry and thunderous beating wings (Lame Deer’s 1969 interview).The seventeenth century Bible scholar Samuel Bochart penned an in-depth study of the animals in the Bible. He describes how winged serpents are not only a thing of the Old Testament but were still alive in his day: “If on your travels you encounter the serpent with wings who circles and hurls himself at you, the flying snake, hide yourself because of its reputation. Lie down when the snake appears and guard yourself in alarm for that snake’s manner is to go away calm, considering it a victory… There are winged and flying serpents that can be found who are venomous, who snort, and are savage and kill with pain worse than fire…” (Bochart, Samuel, Hierozoicon: sive De animalibus S. Scripturae, Vol. 2, 1794.)

Evolutionary Zoologist Desmond Morris wrote, “In the world of fantastic animals, the dragon is unique. No other imaginary creature has appeared in such a rich variety of forms. It is as though there was once a whole family of different dragon species that really existed, before they mysteriously became extinct. Indeed, as recently as the seventeenth century, scholars wrote of dragons as though they were scientific fact, their anatomy and natural history being recorded in painstaking detail. The naturalist Edward Topsell, for instance, writing in 1608, considered them to be reptilian and closely related to serpents: ‘There are divers sorts of Dragons, distinguished partlie by their Countries, partlie by their quantitie and magnitude, and partlie by the different forme of their externall partes.’ Unlike Shakespeare, who spoke of ‘the dragon more feared than seen,’ Topsell was convinced that they had been observed by many people: ‘Neither have we in Europe only heard of Dragons and never seen them, but also in our own country there have (by the testimony of sundry writers) divers been discovered and killed.’” (from the forward to Dr. Karl Shuker’s Dragons: A Natural History, 1995, p.8.)

Evolutionist Adrienne Mayor spent considerable time researching the possibility that Native Americans dug up dinosaur fossils. But some of the reports she received make a lot more sense if these early Americans interacted with actual dinosaurs, not yet extinct. There is no evidence for sophisticated Ancient Paleontologists. An old Assiniboine story tells of a war party that “traveled a long distance to unfamiliar lands and [saw] some large lizards. The warriors held a council and discussed what they knew about those

strange

creatures. They decided that those big lizards were bad medicine and

should be left alone. However, one warrior who wanted more war honors

said that he was not afraid of those animals and would kill one. He took

his lance [a very old weapon used before horses] and charged one of the

large lizard type animals and tried to kill it. But he had trouble

sticking his lance in the creature’s hide and during the battle he

himself was killed and eaten.” (Mayor, Fossil Legends of the First Americans,

2005, p. 294.) This story conjures up credible visions of the scaly

hide of a great reptile, something Native Americans would not know from

mere skeletons. It was once thought that Woolly Mammoths had flourished

in North America prior to the arrival of humans. But the discovery of

sites where many mammoths were killed and butchered has established the

co-existence of men and mammoths. Perhaps similar evidence involving

dinosaurs will be forthcoming.

strange

creatures. They decided that those big lizards were bad medicine and

should be left alone. However, one warrior who wanted more war honors

said that he was not afraid of those animals and would kill one. He took

his lance [a very old weapon used before horses] and charged one of the

large lizard type animals and tried to kill it. But he had trouble

sticking his lance in the creature’s hide and during the battle he

himself was killed and eaten.” (Mayor, Fossil Legends of the First Americans,

2005, p. 294.) This story conjures up credible visions of the scaly

hide of a great reptile, something Native Americans would not know from

mere skeletons. It was once thought that Woolly Mammoths had flourished

in North America prior to the arrival of humans. But the discovery of

sites where many mammoths were killed and butchered has established the

co-existence of men and mammoths. Perhaps similar evidence involving

dinosaurs will be forthcoming.The atheistic astronomer Carl Sagan once remarked: “The pervasiveness of dragon myths in the folk legends of many cultures is probably no accident” (Sagan, Carl, The Dragons of Eden, New York: Random House, 1977, p. 149). Indeed he felt compelled to address the similarity to the great reptiles of the Jurassic era and “explain them away.” How could Sagan do this? Peter Dickinson stated, “Carl Sagan tried to account for the spread and consistency of dragon legends by saying that they are fossil memories of the time of the dinosaurs, come down to us through a general mammalian memory inherited from the early mammals, our ancestors, who had to compete with the great predatory lizards.” (Dickinson, Peter, The Flight of Dragons, New York: Harper and Row, 1979, p. 127). Thus Carl Sagan believed that we evolved not merely our physical bodies, but also memories “uploaded” from our mammalian ancestors!

No comments:

Post a Comment